The biggest battle Abraham Lincoln fought early in the Civil War was simply to find generals who would fight. Northerners wanted a bloodless victory, and Union generals obligingly paraded their troops around grandly but did not pursue physical confrontation with the encroaching enemy. Ulysses S. Grant and his favorite lieutenant, William Tecumseh Sherman, broke the mold. During his campaign to burn Atlanta and “make Georgia howl,” Sherman also wrote one of the most original and trenchant letters in American military history, setting forth the case for what today might be called “total war.”

“War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.”

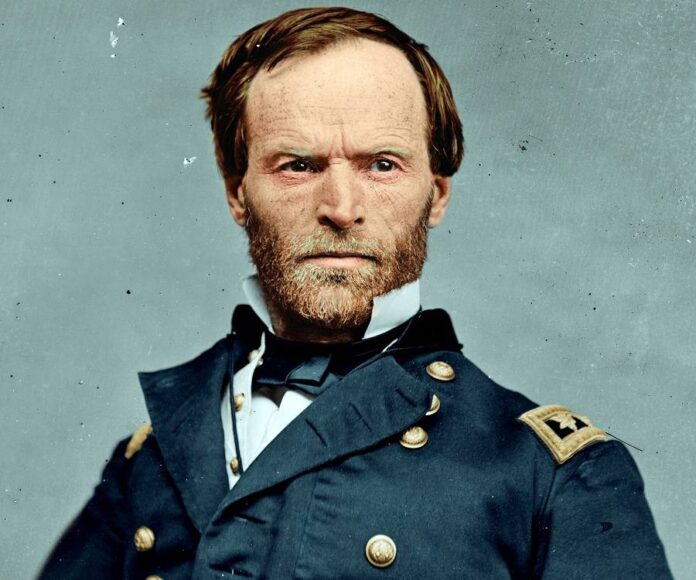

He was one of the more remarkable geniuses to rise unexpectedly to power in that era, this chain-smoking, feisty, intellectual, fast-talking redhead from Ohio. He deftly drove Rebel armies back into siegeworks in Atlanta, a city of just 10,000 people at that time, then took the city and turned his army eastward, breaking loose from his supply lines and marching to Savannah and the sea. This astonishing accomplishment still evokes Southern loathing and Yankee pride.

But before leaving Atlanta, Sherman banished all its civilians, outraging the city’s mayor and leading gentlemen who appealed to Sherman’s common humanity and compassion for the elderly and infirm. But Sherman — a man who loved the South but despised the rebellion — penned a blunt, sharply-reasoned answer. On September 12, 1864, he wrote from his “Headquarters … in the Field”:

“Gentlemen, I have your letter of the 11th, in the nature of a petition to revoke my orders removing all the inhabitants from Atlanta. I have read it carefully, and give full credit to your statements of the distress that will be occasioned, and yet shall not revoke my orders, because they were not designed to meet the humanities of the case, but to prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside of Atlanta have a deep interest.

“Now that war comes home to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition, and moulded shells and shot, to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee.”

“We must have Peace, not only in Atlanta, but in All America. To secure this, we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war, we must defeat the rebel armies which are now arrayed against the laws and Constitution that all must respect and obey. To defeat those armies, we must prepare the way to reach them in their recesses, provided with the arms and instruments which enable us to accomplish our purpose.”

He then wrote words famous to any student of war:

“You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to Secure Peace. But you cannot have Peace and a Division of our Country. If the United States submits to a Division now it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is Eternal War.

“You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.”

“The United States does and must assert its authority, wherever it once had power; for, if it relaxes one bit to pressure, it is gone, and I believe that such is the National Feeling. … Once admit the Union, once more acknowledge the Authority of the National Government, and, instead of devoting your houses and streets and roads to the dread uses of war, I and this army become at once your protectors and supporters, shielding you from danger, let it come from what quarter it may. I know that a few individuals cannot resist a torrent of error and passion, such as swept the South into rebellion, but you can point out, so that we may know those who desire a government, and those who insist on war and its desolation.

“You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride. We don’t want your negroes, or your horses, or your houses, or your hands, or any thing that you have, but we do want and will have a just obedience to the laws of the United States. That we will have, and, if it involves the destruction of your improvements, we cannot help it.”

He reminded them in his blunt fashion that the Southern people had brought war upon themselves while hoping it would remain distant, on front lines never seen. The North did not initiate aggression, but rather:

“[T]he South began war by seizing forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, etc., etc., long before Mr. Lincoln was installed, and before the South had one jot or tittle of provocation. I myself have seen in Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi, hundreds of thousands of women and children fleeing from your armies and desperadoes, hungry and with bleeding feet. In Memphis, Vicksburg, and Mississippi, we fed thousands upon thousands of families of rebel soldiers left in our hands, and whom we could not see starve.

“Now that war comes home to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition, and moulded shells and shot, to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee, to desolate the homes of hundreds of thousands of good people who only asked to live in peace at their old homes, and under the Government of their inheritance. But these comparisons are idle. I want peace, and believe it (can) only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect and early success.

“But my dear sirs when Peace does come, you may call on me for any thing. Then I will share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter.”

He concluded by reaffirming his order to evacuate Atlanta:

“Now you must go, and take with you the old and feeble, feed and nurse them, and build for them, in more quiet places, proper habitations to shield them against the weather until the mad passions of men cool down, and allow the Union and peace once more to settle over your old homes at Atlanta.

“Yrs., in haste,

“W.T. Sherman”

Thus, as a matter of humanity and practicality, Sherman erased the artificial distinction held by Southerners between armies in the field and their industrial and civilian power bases back home. When nations go to war, they go completely, and only total war can vanquish them, he said.

His strategy paid off handsomely. Lincoln was reelected in large part because of Sherman’s successes, and within seven months, Southern generals had surrendered their armies. The pathetic Jefferson Davis, “president” of the so-called Confederate States of America, was caught fleeing, wearing women’s clothing as a disguise, and was imprisoned in leg irons. The total war advocated by Sherman and Grant brought the war to a faster and more decisive end, closing this bloody chapter of American history.