Simi Valley Police Chief David Livingstone, a 33-year veteran of the force, says that in 2009 and 2010, officers “started to notice a lot of OxyContin, also heroin, becoming much more abused in the city, and we also saw an increase in overdose deaths. Those two things in combination made us realize it was a big problem.”

It especially alarmed them to see opioid use spreading to kids of high school age and even younger.

“As we did surveillance, the discovery of the younger age group using these drugs was a surprise,” Livingstone says. “Technology has made it much easier for young people to access drugs. Kids can sit at home and call a heroin delivery service in the same way they can order pizza and have it brought to the house.”

These drugs, he says, are coming over the southern border with Mexico and also from China and Europe — and have made their way into once-safe communities like those in Ventura County. Shawn Wilson, Substance Use Navigator for Adventist Health Simi Valley emergency department, says not a day goes by that he doesn’t encounter someone with an addiction issue.

“In the last five years, there has definitely been an increase in the popularity of opioid use, specifically fentanyl, which is laced in everything, especially street drugs, and the kids who are using street drugs aren’t aware of it,” he says. “Right now, substance abuse across the board is at an all-time high. What people are buying on the streets — what they think is straight heroin or methamphetamine — if it’s laced with fentanyl, it’s a fatal combination.”

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, each year an estimated 20 million Americans abuse opioid drugs. Two out of three overdose deaths involve natural or synthetic forms of opioids, including heroin, fentanyl (considered the deadliest and most widely available), oxycodone, codeine and morphine. The opioid crisis, deemed a public health emergency in 2017, has been shown to impact people from all backgrounds.

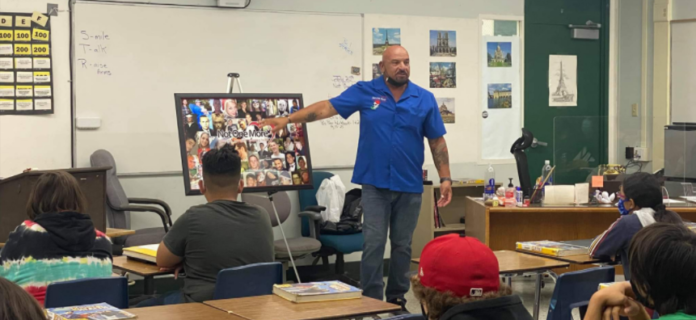

“There’s no limit to whom opioid addiction will affect,” said Pat Montoya, president of the Simi Valley–based nonprofit Not One More, which was founded nearly a decade ago by concerned parents, families and friends who took notice of the rising drug problem sweeping the community — and decided to do something about it.

Not One More’s mission is “to raise awareness and prevent drug abuse in the community through education and community partnerships.” While not a rehab center, the organization directs addicts to recovery resources where they find help they can use.

“We’re a place people can come and not feel alone,” Montoya said in a recent phone interview with the Conejo Guardian.

Montoya’s first exposure to the opioid crisis in his community was an article he read in the local paper about a heroin overdose. Looking into the story more closely, he discovered the victim wasn’t the kind of person you would typically suspect as a heroin addict.

“They are local kids, athletes, from homes with loving and supportive families,” he said. “We felt a need to get the news out to the public because we were concerned about what we were seeing as far as an uptick in drug overdoses and addiction to heroin, opioids, prescription drugs and methamphetamine.”

Not One More was launched following the loss of co-founder Melissa Siebers’ daughter to a heroin-related accident. Montoya and Susan Klimusko helped bring this new kind of drug problem to the attention of the city council, and as a result, the police formed a heroin task force to look at ways to deal with the problem as a community. In addition to enforcement, the police sent resource officers into schools to talk to kids.

“Education is the most important part of this issue, and it starts in the home with family,” Livingstone says. “We need to get the parents the tools to know what to look for. A lot of parents find out their child is addicted to drugs after it’s too late. There has to be structure, and the police are part of that; they are in a way an extension of the family, but finding out how we work effectively together is the harder question.”

Not One More has helped build some of those bridges.

“Partnering with groups like Not One More is critical, as it has helped us to better understand the drug problem,” the police chief says. “Enforcement is only going to go so far. If there are no treatment resources after an arrest, there’s no incentive for addicts to try to get clean.”

Not One More primarily works with teens. Since its inception in 2012, Not One More has expanded to include 16 chapters in states across the country, from Seattle and New York to Pennsylvania and Alabama.

“The cycle of drug addiction for many starts with abusing prescription drugs,” said Montoya, sharing the story of his own son, a healthy high school football player who succumbed to heroin addiction after getting hooked on opioid pain medication.

Aliza Thomas, who was born and raised in Newbury Park, relates all too well to the Montoya family’s struggles. A former drug addict, Thomas now serves on the board of Not One More and is author of the book Junkie, published under the pseudonym Tommy Zee. She speaks at local middle and high schools and shares her difficult but ultimately inspiring journey to sobriety.

“These drugs change the brain chemically, and the kids believe they are invincible,” Thomas said in an interview with the Guardian. “If parents are leaving opioids in the medicine cabinet open to everyone in the house, the kids are going to find them.”

Thomas noted that eight out of ten alcoholics are victims of sexual abuse and that drug addiction is often a “sub-branch” of domestic and sexual abuse.

“Finding the root of the problem is key,” she explained, “and from there, we can work with addiction recovery and mental health plans.” Thomas further emphasized the importance of spirituality, meditation, and sharing one’s stories during the recovery process.

Central to the mission of Not One More is personal testimony, and Simi Valley native Chris Pickett has spent the past two years of his sobriety relating his story to people across age groups and state lines. Hailing from an upper-middle-class family with two loving, supporting parents in the home, Pickett, at age 13, began abusing his mother’s Vicodin prescription to treat the debilitating migraine headaches he’s had from an early age.

He later admitted that the “void” he was attempting to fill with drugs was, in fact, a hole the drugs themselves helped to create. Yet at the time, the high proved too irresistible to the young aspiring musician, and the prescription pills ultimately served as a gateway drug to harder substances, including heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine.

By his mid-20s, Pickett had a criminal record, had cycled in and out of rehab, and was spending years in what he described as a “comfortable misery.”

“It was really, really easy to obtain opioids on the streets,” said Pickett. “You could get three or four prescriptions filled in one day.”

By age 18, Pickett was using heroin regularly. “It was cheaper, more accessible, and if the police cracked down on a drug dealer, there was always another one to go to,” he said. “Everybody I knew in my circle of friends either had tried heroin or was addicted to it at that point.”

But in the early 2000s, as authorities began to crack down on pain management clinics where many teens obtained their drugs, prescriptions became less widely available. This led to a huge influx of illegally manufactured heroin coming across the Mexico border, said Pickett.

At age 20, with the help of Alcoholic Anonymous, Pickett got clean and has dedicated his life to the recovery outreach community, working to connect the teenage population — of which roughly three percent is impacted by opioid abuse — with resources for drug addiction and mental health issues.

Thomas and Pickett express grave concern about the increasingly widespread use of fentanyl among young adults, which, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, factors into 19.8% of all overdose deaths.

“This drug is so terrifying,” said Thomas. “Parents need to know how serious this drug is.”

Not One More helps inform parents and kids through services aimed at prevention and education. The nonprofit also works closely with the Ventura County Juvenile Probation Department Diversion program.

“We are receiving so many contacts from around the nation and around the world,” said Montoya. “We base everything we do out of love. We show a lot of love to people in addiction, the families who get involved.”

Not One More: “There’s no limit to whom opioid addiction will affect,” said Pat Montoya, president of the Simi Valley-based nonprofit Not One More, which was founded nearly a decade ago to raise awareness and prevent drug abuse in the community through education and community partnerships.

I was waiting for the “Granny’s medicine cabinet” explanation of how most kids get hooked on opioids . Please stop with that, personal anecdote notwithstanding. They smoke pot and mix it with beer or liquor. The kid with the weed has other interesting stuff. I agree that over the years, heroin was a cheap drug, readily available, so they tried that.

The elderly and the veterans with incurable pain need the legitimate prescriptions, and now doctors have been intimidated into prescribing the effective drugs. Take Tylenol. Because some kids were risk takers and moved on from one high to the next.

Doctors have been intimidated into NOT prescribing effective drugs . They suggest taking Tylenol.